Undersupply myth

Why building less doesn’t push prices up

Synopsis

Australia only adds 1.5–2 per cent new housing each year - a trickle far too small to move national prices. My charts show that rising commencements lift house price growth, while falling commencements cool it. Under-building drives rent stress, not price inflation. Price cycles follow interest rates, confidence and resale stock, not construction volumes.

Introduction

One of the most persistent myths in Australian housing is the idea that high and rising house prices are caused by “not building enough.” It gets repeated because it sounds simple, logical and convenient. But it’s wrong - and the data, including my own charts, shows why.

Let’s start with scale, because this alone exposes the flaw in the popular argument.

Australia has 11.4 million dwellings. Even in our absolute best years, we add new supply at 2–3 per cent — and even that happens only for a year or two at a time. Most years, the build rate sits between 1.5 and 2 per cent. That’s not a flood of new stock; it’s a trickle.

And a trickle is not large enough to meaningfully move the value of millions of established homes. You cannot materially shift a national asset class worth nearly $12 trillion with a 2 per cent annual addition. The maths simply doesn’t work.

So when commentators confidently say that “under-building” is the reason prices rise, they’re confusing supply needed to house people with supply capable of driving price cycles. These are two separate conversations - and my charts make this distinction very clear.

What my charts actually show

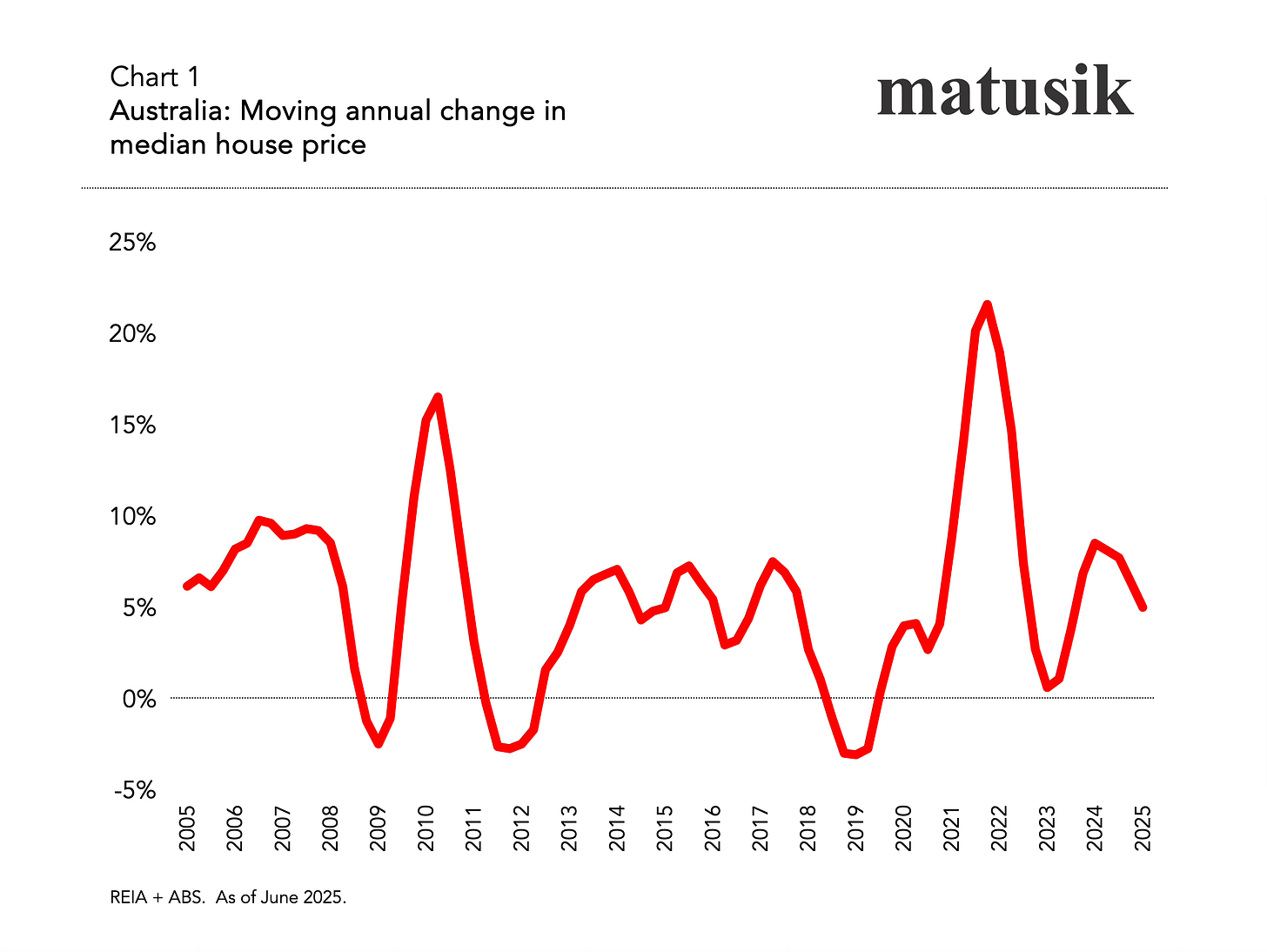

Chart 1 tracks the annual change in median house prices.

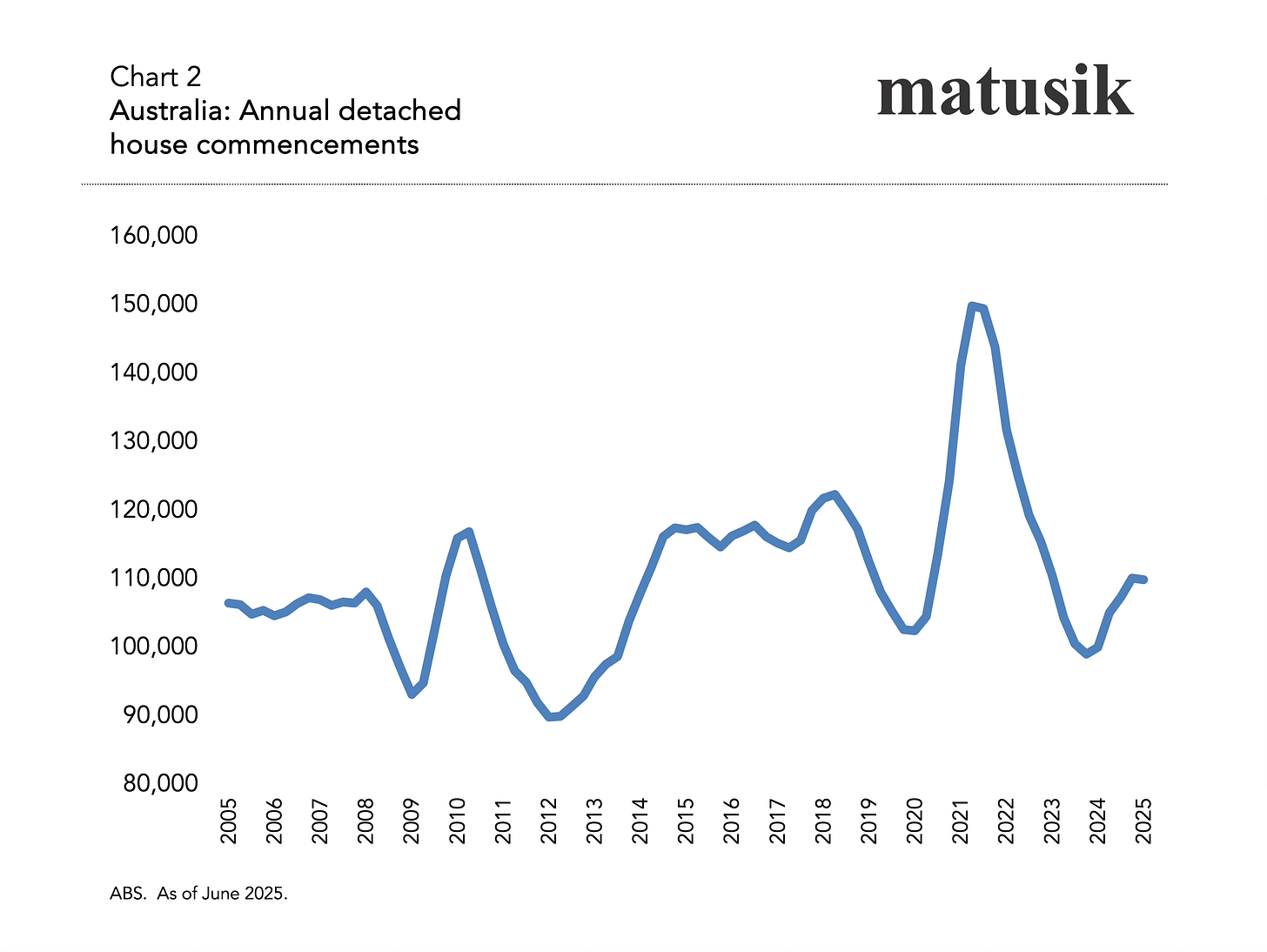

Chart 2 tracks annual detached house commencements.

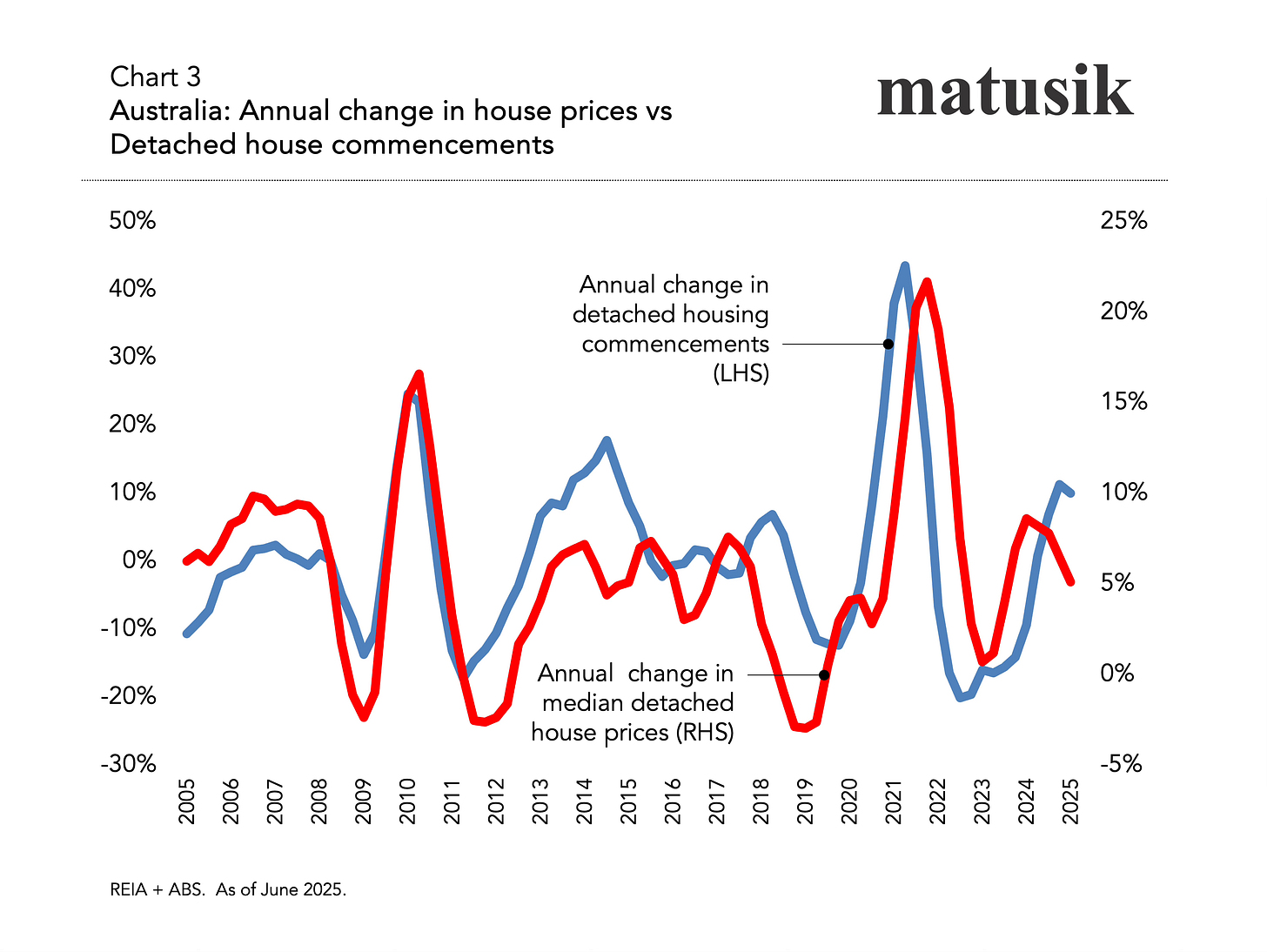

Chart 3 overlays them.

And the conclusion is unmistakable: When detached house commencements rise, house price growth rises. When commencements fall, house price growth slows or turns negative.

That’s the recurring pattern across multiple cycles over the past two decades.

If under-building pushed prices up, the lines would move in opposite directions. But they don’t. They move together. More new supply supports the market. Less new supply cools it.

That is the real relationship - and it’s the exact opposite of the public narrative.

Why under-building is actually deflationary

There are five clear reasons why building less does not fuel price growth - it suppresses it.

1. With fewer new builds, the high-price benchmarks disappear

New detached homes sit at the top of the price tree. They reset expectations and lift comparable values of established dwellings. When fewer new homes complete, those benchmarks vanish. Without the “premium end” pulling values upward, price growth naturally softens.

2. Falling construction weakens the broader economy

Construction is one of Australia’s biggest economic engines. When commencements fall, trades, suppliers, and associated industries slow down. That means less income, lower borrowing power and weaker buyer sentiment - all of which reduce upward pressure on prices.

3. A shrinking supply pipeline reduces investor demand

Investors respond to confidence, liquidity and future rental supply. When new construction dries up, the future rental pool thins. Yes, rents rise, but predictability falls - and so does investor appetite. When investors step back, price momentum declines.

4. Low new supply lowers turnover - and low turnover means weaker price acceleration

New builds provide the stepping stones that let households move: FHBs into entry stock, families into new houses, downsizers into fresh low-maintenance homes. When that pipeline shrinks, people stay put. Markets with low turnover simply don’t produce sustained price surges.

5. Undersupply shows up as rent stress, not price inflation

When population grows faster than new supply, the first pressure point is rentals - not prices. Prices depend on buyers with capacity, not just people needing shelter. Undersupply pushes more people into renting for longer, delaying their ability to buy and dampening credit expansion. That suppresses price growth rather than igniting it.

Now, lets layer up last week’s data dump

ABS figures show the value of Australian housing rose $317 billion in the September quarter, even as dwelling approvals fell 6.4% in October. At the same time, the federal government is now 70,000 homes behind its 1.2-million target.

If under-building caused price inflation, slowing approvals should pull prices up even faster. But the opposite is true. These price gains are happening in spite of, not because of, construction shortfalls.

Prices move when interest rates fall, confidence improves, investors return, and resale listings remain tight.

They move because of money, mood and momentum - not the volume of new homes entering the system.

Undersupply is a housing problem, not a price-cycle driver.

Listen

End comments

We absolutely need more supply - especially affordable supply - to house people, reduce rental stress, and support household formation. But we should stop pretending that boosting construction by 10,000 or even 50,000 dwellings a year will magically rewrite national price trajectories.

Under-building explains rent stress. It explains household formation pressure. It does not explain price growth.

Until policymakers and commentators separate those two conversations, we’ll keep misdiagnosing the problem - and keep missing the real levers that shape Australia’s housing market.

Save 20% - only a few days remain

And thanks to all you peeps that took up the 35% Black Friday Sale Offer and in the spirit of the season all can save 20% on all my Ready Reckoner Reports for the next couple of days. Offer ends Friday 12th December. Ho ho ho.

Use the Save7Days coupon to save 20% on my Ready Reckoner Reports.