Regional Revival?

If you find a 30-something in a country town, photograph it

Synopsis

Regional Australia hasn’t solved its young-people problem. The COVID-era ‘youth boom’ was a statistical mirage, and towns under 50,000 are again losing 25–40-year-olds to the capitals. But some small towns are turning the tide - by building the right housing and career ladders, childcares and identity. Young workers don’t stay by accident.

Introduction

Every few years several commentators announced that regional Australia has finally solved its “young people problem”. Such babble was based on one cheery number: that the regions gained tens of thousands of 25-to-40-year-olds in the five years to the 2021 Census.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: that figure is more illusion than renaissance.

Revisit: More regional hullabaloo

To recap the 2021 Census was taken in the middle of lockdowns, restrictions, remote work mandates and border quirks. Many young adults who would normally pack up for the big smoke simply couldn’t. It wasn’t a wave of returnees revitalising the small towns - it was a temporary pause in something that has been happening for decades: the steady thinning-out of the working-age cohort in towns under 50,000 people.

And the latest ABS data makes that hard to ignore.

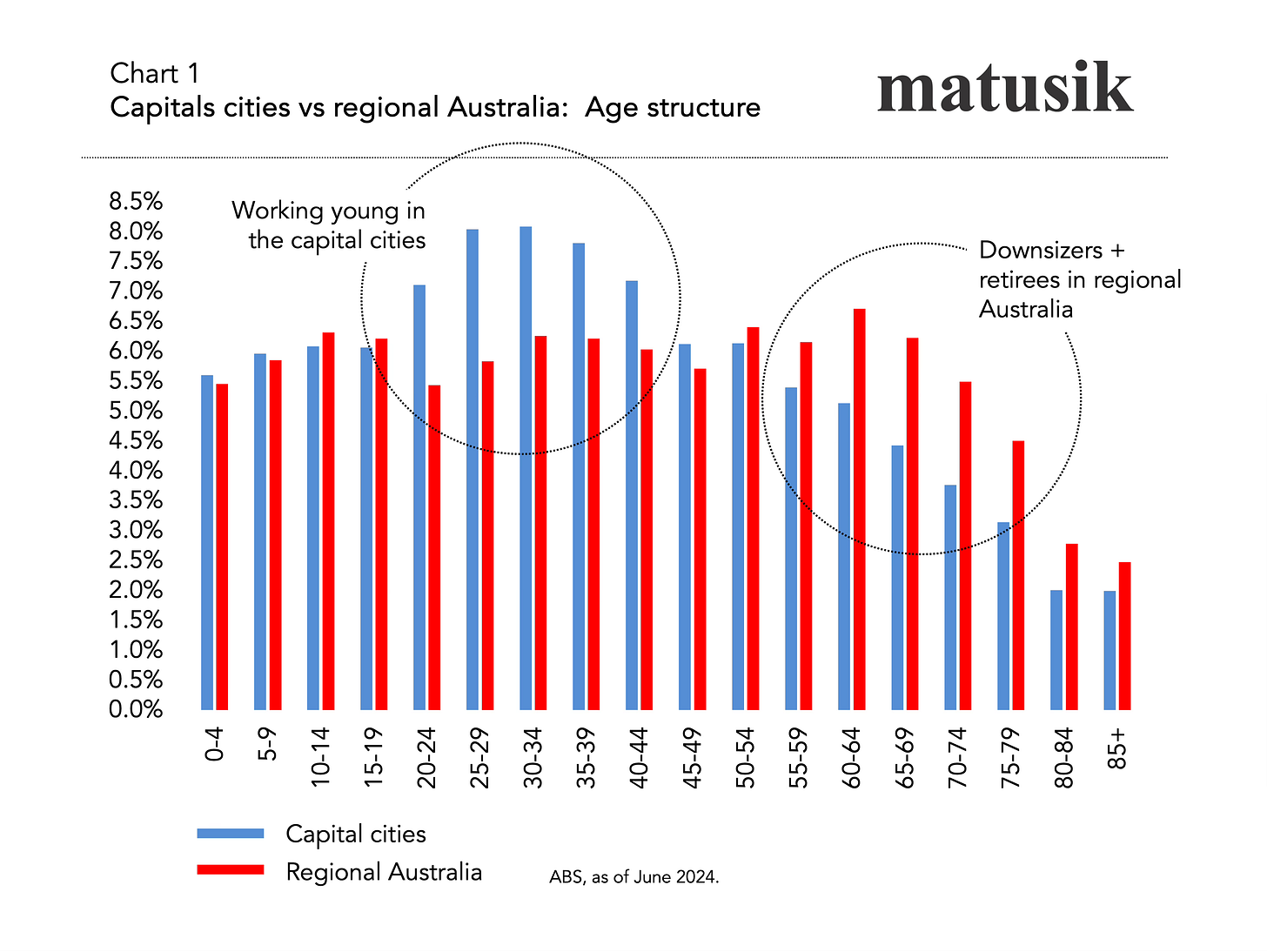

As of 2024, only 30% of residents outside Australia’s capitals are aged between 20 and 44. In the capitals, it’s closer to 40%. The median age in the regions is now 42, versus 36 in the cities.

In other words: regional Australia isn’t just older - it’s missing a big chunk of the workforce in the absolute prime of skill-building, income growth and family formation.

That’s the real story. And for the small places - between 5,000 and 50,000-population towns scattered across the country - the challenge is sharper again. Many still lose 25-40-year-olds faster than they attract them, and the post-COVID bounce was more about reduced exits than surging arrivals.

So the real question isn’t, “Has the brain drain stopped?” It hasn’t.

The more pertinent inquiry is: Where is it actually working — and what are they doing differently?

Listen

Still struggling with the back to work slug. The last thing you want is something more to read. Kool. I understand, my 3 minute reading has got you covered.

The problem beneath

When younger people leave regional towns, it’s rarely because they dislike the place.

Studies show they leave for one of four reasons:

1. Career depth. Many small towns can offer a job but not a ladder. In cities, you can change employers without changing suburbs. In the regions, that often means moving interstate.

2. Education + training. Uni or TAFE options are usually elsewhere. Once an 18-year-old leaves, the odds of them coming back after graduation are slim.

3. Amenities + services. Young families go where the childcare spots exist, where there’s a bulk-billing doctor, decent sport and recreation, and places for kids to grow up without a 40-minute drive for everything.

4. Housing mismatch. Ironically, some small towns don’t have the housing young adults want - smaller dwellings, good rentals, modern stock - even if the blocks are cheap.

These are structural issues. If a town loses too many 25-40-year-olds for too long, its economy ages, labour shortages grow, and the services needed to attract young people shrink further. It becomes a cycle.

But some towns are breaking the cycle - and not through luck.

Five places showing promise

Here are a few examples worth watching. Not all are booming, but each is doing something that flips part of the script.

1. Horsham, VIC – A town trying to hold its 30-somethings

Horsham isn’t immune to the ageing trend, but it’s one of the few places using data to fight back. Local planners openly track migration by age and now shape policy around retaining the 25–40 cohort. They’re investing in recreation infrastructure, childcare capacity and small business spaces - the kind of liveability ingredients that make it realistic for young adults to stay without sacrificing lifestyle or opportunity.

2. Dungog, NSW – A small town for the hybrid worker

Dungog’s growth isn’t accidental. It’s close enough to Newcastle for hybrid work, has good connectivity, and offers a lifestyle that appeals to 30-somethings who want community with a capital C. It never tried to be “mini-Newcastle”; it leaned into what makes it Dungog - and that’s working.

3. Charters Towers, QLD – Lessons in what happens if you don’t adapt

Charters Towers tells the opposite story. With ageing demographics and limited modern housing stock, the town struggles to turn job opportunities into new residents. It’s a reminder that a strong employment base alone isn’t enough - if rentals are scarce or tired and childcare queues are long, young families will keep driving past to larger centres.

4. Tumby Bay, SA – Childcare as an economic strategy

Tumby Bay has recognised that childcare isn’t a social service - it’s economic infrastructure. Plans for new capacity and more diverse housing types are designed specifically to support dual-income households and early-career workers. The small-town “we’re just old retirees” narrative is being rewritten deliberately.

5. Chapman Valley & other resource regions – From FIFO to local

Some resource-adjacent shires are reframing growth by tying projects to local job creation and apprenticeships rather than relying on FIFO. It’s early days, but the shift from transient labour to resident labour changes the demographic equation quickly.

Sadly as the list above shows - and kudos to the regional places that are giving it a go - examples are short on the ground. It might be too hard? Or just not of importance to the locals or decision makers? Or maybe the gravitational pull of the big smoke is just too strong?

I reckon it is more head in the sand than anything else. But make no mistake it will take concerted effort to reverse - even slightly - this exodus trend.

Five key lessons for keeping 25–40-year-olds in small towns

Provide the housing they’ll actually live in - modern rentals, smaller dwellings and walkable locations matter more than big blocks with old houses (that need a lot of work) because many of them just don’t want this.

Compete for young workers on purpose, not by accident - plan for them the way most towns have spent a decade planning for retirees.

Treat childcare and health as economic infrastructure - because young families won’t stay where basic services don’t exist.

Show real career progression, even if it’s only a couple of visible rungs - young adults stay where they can grow, not just work.

Build identity, culture and connectivity - hybrid work hubs, events, sport and creative life keep people anchored far more than another housing estate ever will.

End note

Here’s the twist in 2026: with interest rates likely to sit tight - or even nudge higher (and more on that next week) -big-city housing affordability will continue its slow-motion nose-dive. That means the working young may finally glance at regional Australia and think, “Hmm… maybe.”

But they won’t flock anywhere just because the rent or mortgage is cheaper. They’ll be picky. They’ll compare housing typology and quality, childcare waitlists, job ladders, café culture and hybrid-work setups. And the towns that tick those boxes will start collecting the sightings.

If you find a 30-something in a country town, photograph it - because the places that want more of them will need to earn it.