More buyers, same bricks

Whilst the government pumps demand, the RBA should push lenders to actually fund new supply.

Synopsis

The government has just expanded the Home Guarantee Scheme, while the RBA held rates steady due to inflation risks from fiscal stimulus and an undersupply of new housing. This missive explores how the HGS shapes demand, how modular and backyard housing could help supply, and how the RBA governor can influence the path forward.

Government moves & macro backdrop

Last week brought a double-barrel of housing news. The Federal Government announced a dramatic relaxation of the Home Guarantee Scheme, throwing the doors open for thousands more to enter the property market with only a 5% deposit and no lenders’ mortgage insurance. At the same time, the Reserve Bank held the cash rate steady, with the governor warning of inflationary risks - driven not just by broader government spending but by the persistent undersupply of housing.

Australia’s housing market is stuck in a tug-of-war between demand-side stimulus and supply-side blockages. Policy continues to add fuel to the demand fire, while approvals, construction bottlenecks, and costs keep new supply constrained. The question, as ever, is whether we can unlock new stock fast enough to offset the heat.

Listen

What the Home Guarantee Scheme means

The Home Guarantee Scheme (HGS) is designed to lower the barrier to entry. It allows eligible buyers to secure a home with a small deposit while avoiding the extra impost of mortgage insurance. For many younger households, saving a 10% deposit - let alone a 20% one - is near impossible; the scheme recognises this reality.

The recent relaxation strips away many of the previous guardrails. There are no longer income caps or fixed quotas. The property price caps have also been lifted sharply — for the capitals and regional centres it jumps from $800,000 to $950,000, and in Sydney it leaps from $900,000 to a staggering $1.5 million.

That means a much wider range of dwellings now qualify. But it also begs the question: how did we get here, where a “first home buyer” needs to borrow close to a million dollars across much of Australia, and almost one-and-a-half million in Sydney, just to squeeze onto the ladder?

It’s a sobering reminder that the affordability crisis is already baked into the system.

Expected impacts on the housing market

With the expansion of the HGS, more buyers will now be able to compete in the market. The lifting of property price caps effectively moves the goalposts, widening the pool of eligible dwellings and buyers.

The immediate impact of the changes is a significant increase in demand, particularly in the entry-level and lower-middle brackets. Lower deposit hurdles mean households can jump sooner rather than later.

Independent modelling suggests the expanded scheme could bring forward between 20,000 and 40,000 buyers in its first year alone — the equivalent of around 4% to 7% of all annual housing sales. And because most first home buyers naturally target the more “affordable” segments, the pressure will be concentrated on townhouses, smaller detached houses, and smaller apartments priced just below the new caps.

With supply already inelastic in the short term, this surge in demand will translate directly into higher prices. Industry modelling suggests national prices could rise by 3.5% to 6.5% by 2026, and in the first home buyer hot spots the lift could be closer to 10%.

In many cases, the gains from avoiding mortgage insurance will be dwarfed by the jump in purchase prices. For example, a buyer might save $25,000 in insurance premiums, only to pay on average $50,000 extra - and often much more - on the property itself.

This creates a redistribution effect. Many of the scheme’s beneficiaries would have bought eventually — through mortgage insurance or family help — but now they are entering earlier and bidding harder.

The real beneficiaries, at least in the short run, may be the sellers, who enjoy higher prices. Meanwhile, lower-income would-be buyers risk being pushed even further out of reach. The scheme might nudge home ownership rates a fraction higher, but it risks making the overall affordability gap wider.

There is also a financial stability angle. With just a 5% deposit, new buyers are highly leveraged. Even a modest correction could push them into negative equity. Because the Commonwealth stands behind these loans, the exposure isn’t just personal — it’s national. Estimates suggest the government’s contingent liabilities could climb into tens of billions under stress scenarios. In other words, while accessibility improves, the system as a whole takes on more risk.

Unless supply can expand — through faster approvals and in modular construction plus backyard housing (two of my bugbears) — this injection of demand will only reinforce the same old cycle: easier to buy in, but dearer to own once you do.

Where supply can come from?

Australia’s housing system cannot rely solely on large greenfield estates or slow-moving high-rise towers. The sweet spot lies in small-scale, high-utility supply - dwellings that can be slotted into existing suburbs with speed and efficiency.

Three options stand out:

First, the townhouse remains the backbone of infill development. It is mortgage-friendly, fits within most local planning schemes, and has a ready resale market. Buyers, mostly, understand it, banks like it, and developers can model feasibility with confidence. But, for mine, when in comes to infill townhomes they be on freehold title. Doing such would eliminate much of the remaining buyer resistance.

Second, modular housing - when fixed to a slab and built to code - offers a faster, more predictable way to deliver dwellings. It reduces construction timelines, mitigates labour shortages, and can be rolled out at scale. Yet banks and valuers remain cautious, often restricting lending or shaving LVRs. Overcoming that hesitation is essential if modular is to become mainstream. It is my understanding that only one of the major banks currently offer a 80% mortgage on a modular build.

Third, the rise of backyard housing (BYH) and tiny homes (in essence a mobile home) could unlock under utilised middle-ring and suburban land. It is estimated that up to 1.4 million backyards across Australia have the spare capacity to host a secondary dwelling of 50–100m². In some cases, it could be a granny flat; in others, a small modular home or even a movable dwelling. The challenge is finance, costs and planning. Councils often block or delay approvals, state governments charge way too much when it comes to infrastructure charges, and banks refuse to treat tiny homes on wheels as proper collateral.

Just released

Gold Coast and Brisbane out now, and the other eight SEQld LGAs are in workshop, rolling out in the coming weeks.

Matusik Ready Reckoners: 26 pages, 24 charts/tables. Executive summary; detached, attached and land markets; rental; buying–renting affordability; property clock; population growth; current/potential supply; future demand by dwelling type; key economic indicators; ten major infrastructure projects. All host ten years worth of data to June 2025, plus forward estimates too.

Paid subscribers save 20%. Coupon below the paywall. Not a paid sub? Well you can change that at via red button at the end of this post.

Now back to the RBA.

The RBA’s influence

While the RBA does not dictate which housing forms banks lend on, the governor’s pulpit carries weight. Each RBA machination is almost always front page news. By highlighting modular construction, backyard housing, tiny homes and often small-scale infill as legitimate parts of the solution, the RBA can encourage lenders and regulators to adjust their stance.

If the governor signals that flexible lending models for compliant modular or backyard housing would improve financial stability by reducing price pressures, APRA and the banks will take note. This is not about formal directives but about moral suasion—the quiet but powerful ability to shape expectations and set priorities.

Imagine a central bank governor openly calling on lenders to embrace modular housing finance, or urging councils to encourage the provision of backyard dwellings. That sort of leadership could change the tone of the national conversation, shifting us from a demand-fixated cycle to a supply-focused.

The backyard home or tiny dwelling is the most radical of the two solutions (apart from modular) but also the most constrained. Without active support, sensible costs and bank recognition, it remains a niche. Yet if these barriers were eased, the latent capacity in middle-ring and suburban backyards could become one of the biggest sources of new housing supply in the country.

To recap, there are up to 1.4 million under-utilised spaces lying dormant in mostly great locations - which could hold very affordable and appropriately sized digs - across the country.

What should happen next

Australia needs to unlock new supply channels. That means encouraging freehold townhouse development, legitimising and financing modular construction, and clearing the path for backyard housing.

Governments should streamline planning rules, help reduce costs for small dwellings, and run pilot projects that show lenders and valuers these products work. Banks should be encouraged, even nudged, to treat compliant modular stock and backyard housing solutions on the same terms as traditional homes.

Councils should be set ambitious targets for backyard dwelling approvals, recognising them as legitimate infill. Heck why not get proactive and contact land owners letting them know what is possible. Most of us ache for ‘community’ these days. One of the ways to achieve this is to facilitate ‘inclusive’ infill housing.

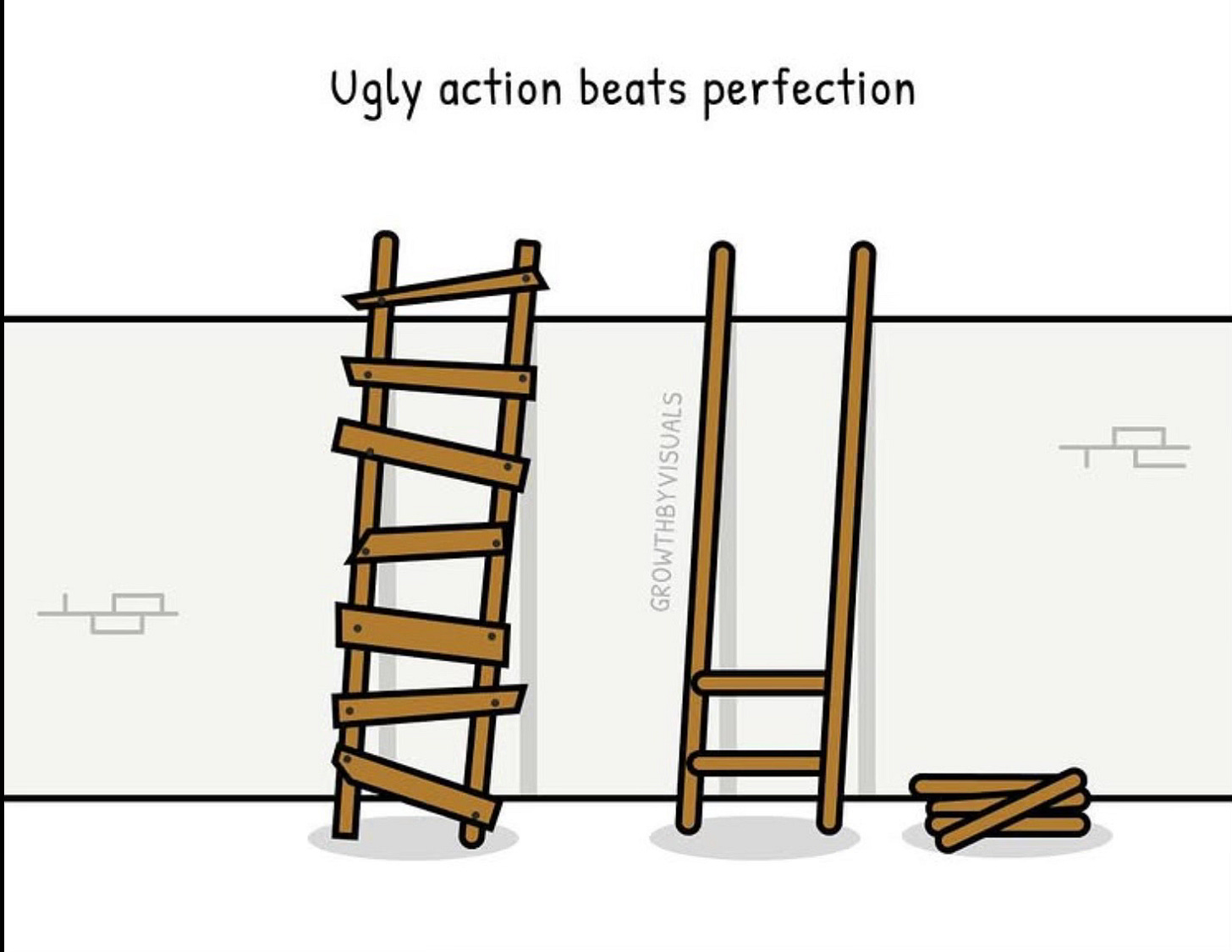

But to even start this process the town planning fraternity will need to accept that “perfection is often unrealistic and that action is more valuable than waiting for an ideal outcome”. Or to maybe misquote George S. Patton: “A good plan violently executed now is better than a perfect plan next week”.

In short, backyard homes now are better than new apartments, fingers crossed, in say ten years. And importantly a modular home or BYH isn’t forever. Moreover, tiny homes can move at a instance. Regardless of form, these infill solutions can easily make room for more ‘perfect’ builds in the future when the apartment mathematics feasibly combine.

And for now the RBA governor should use her platform to remind the nation much more can be done to increase new housing supply, especially given that the biggest road block to this new supply is financial.

And imagine if the HGS - as of the start of this month - was, say halved, and now only applied to modular builds and/or backyard housing solutions.

End note

The expansion of the HGS lowers barriers and accelerates home ownership. But it really just brings demand forward, and in this case, during a time of very tight supply. Ironically it risks fuelling the very inflation it seeks to ease.

The answer lies not in endlessly stoking demand, but in unlocking new ways to build, densify, and reimagine housing supply - from townhouses, true, but moreover, modular builds and backyard homes in the very suburbs that need them most.

And unless we do this, then expect interest rates to remain higher than they really should be.

For mine, they really do need to keep falling, because the important things are heading the wrong way. And I will lay out what I think is in store over the next two weeks. Bated breath?